As I mentioned last week, some of my shop time has been spent getting things ready for spring. In particular, this has meant making sure I have enough, and the right kind, of “additional housing” (hives and frames) for the bees.

Langstroth’s Hives

While I’ve got a top-bar hive box built, I don’t have any bees in it yet. I’m waiting to see if I can catch a swarm to fill it. The main portion of my gear is the so-called “Langstroth Hive” system. It’s named for Rev. Lorenzo Langstroth (1810-1895), who discovered a peculiar notion called the “bee space,” which I’ll describe in a bit.

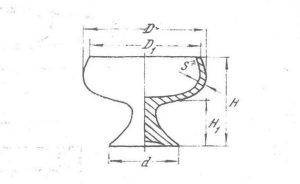

Langstroth’s system involves the use of boxes (“hive bodies”) filled with removable frames, on which the bees build their comb. The boxes mimic the hollows of trees, which the bees would use “in the wild.” The frames provide guidelines of a sort for the comb, otherwise it would be all swirly and convoluted. Pretty, but of no use to the beekeeper, because we can’t remove it intact.

The hive bodies come basically in three sizes: deep, medium, and shallow. (We’re nothing if not inconsistent…) The deep is a bit over nine and a half inches tall; the medium is a little more than six and a half inches, and the shallow is about five and three-quarter inches. The length and width of all the boxes in a hive is the same, but they come in two “sizes”: eight-frame, and ten-frame. This, obviously, describes the number of frames in a box.

The three sizes are used for different purposes: deeps are primarily brood boxes, where the queen will lay her eggs. Mediums are sometimes used as brood boxes, but more often they’re placed atop the deeps, for the bees to store honey. And shallow boxes are almost exclusively used for honey.

Bee Space

The main innovation introduced by Langstroth was the concept of “bee space.” Bees are notorious for two types of “building”: comb, and propolis. Comb is, well, comb–where they lay eggs, or store pollen, or put honey. They’ll build it off the tops, sides, or bottoms of things–basically, if they think they’ve got room to put in a bit of honeycomb, they’ll try to build some.

Propolis, on the other hand, is sort of a combination bee-glue, paint, and spackle. In essence, it’s plant resins that they’ve collected, but can’t turn into pollen or honey. It tends to be quite sticky. The bees use it to cover the inside of the hive (it may have some antibacterial properties), to plug “leaks” (if there’s a crack in a hive body, or between two hive bodies), and to make things inside the hive immobile. I generally can’t do a hive inspection without scraping off enough propolis to make a decent-sized ball of the stuff.

The deal is, if there’s more than about a bee’s thickness of space, the bees will build some comb. If there’s less than a bee’s thickness of room, they’ll try to fill it with propolis. But if the spacing is just right, they pretty much leave it be.

Langstroth observed that “just right” is between 1/4 and 3/8 inch, and sized his boxes and frames to leave just that amount between everything. The boxes and the frames (to guide the bees in making comb) are sized just so, and they maintain the bee space.

But Why?

The reason we’re concerned with keeping excess comb and propolis out of the hive is so that we beekeepers can do our regular inspections. If the bees have built “burr comb,” which juts out from an existing frame, they may stick multiple frames (or boxes!) together. So-called “cross comb” is when they build their comb “sideways,” across multiple frames. This makes it impossible to remove the frames neatly, and generally results in ticked-off bees.

The propolis is less of an issue in that sense, but it has the tendency to glue the frames down inside the boxes, making them difficult to remove. Occasionally, something will get into the hive that the bees don’t want, but can’t remove themselves (the occasional mouse, that sort of thing). In those instances, they’ll propolize the entire thing, also making it difficult to remove–and making quite the mess.

The hive inspections are for multiple purposes. First and foremost, it’s to check on the health of the hive–is the queen healthy and laying lots of eggs? Is there a disease issue to be dealt with? Are there parasites that need to be treated for? Second, we’re looking at how well the hive is working–whether they’re bringing in sufficient pollen and nectar, building enough comb in the right places, and such. Third, we’re looking to see if the bees are preparing to swarm or to replace their queen–sometimes this is good, sometimes not so much. There are things the beekeeper needs to do, in either situation.

Lastly, and certainly not least important, is we’re checking on the honey stores. This is both for ourselves, as the beekeepers, but also to see that the bees have enough to get themselves through any dearths or through the winter (when there is no nectar flow).

Building Boxes

All of this is a long-winded way of saying I spent the better part of a couple of days making new boxes and frames. My “active supplies” included six deeps in use (three per hive–this will probably decrease to two each, by the end of the year), plus two mediums with drawn frames, two mediums with partly-drawn foundation, two shallows with drawn frames, and two more mediums and a deep with empty frames.

After a weekend building stuff, I’m up to ten deeps total, eight mediums, and two shallows. There are frames for everything, plus enough foundation to go around. (Foundation is a thin sheet of wax for the bees to use as a starter.) I’ll have to spend a snow day or two installing all of the foundation, but that’s a task for later.

Curiously, of all the things that could happen while building the boxes and frames (which involves time on the table saw, plus hammering in hundreds of nails), the most serious injury I got while doing all of this was a fairly minor cut, from my own knife, while undoing the strapping holding a bunch of frame pieces together. (Hitting my thumb with the hammer a few times doesn’t count. The nails are pretty small, after all.) But then, if you don’t bleed on it, it’s not a real project, right?

Status of the Bees

Of my two hives, as of mid-January both are still alive and kicking. One of them is definitely stronger than the other–on the warmer days over the last few weeks, they’ve been out and flying en masse. The weaker hive is still there, for now, but may not have enough bees to maintain warmth in their cluster. I’m not concerned about them starving, but they might freeze to death. It would suck, but that’s the nature of things.

Still, even if only one hive makes it, come springtime it’ll be off to the races. I’m certain that the stronger hive, should it make it that far, will be looking to swarm; if I play my cards right, I can make a split from it. That involves finding the prospective queen bees (the brood cells holding queen eggs are distinctive). Then I move those frames, together with a bunch of nurse bees, into a new box, and wait.

If I should make it to spring with both hives alive, I can probably get a split off of each. And if the spring nectar flow is good, I may be able to do that multiple times. My end goal is four to five hives by the end of the season–and at least one honey harvest!

I’m also considering setting up a sponsorship program for the hives–kind of like a CSA for the beehives, or “adopt-a-hive,” if you will. Something on the order of a donation of $X per season, and you’ll get email updates and photos of the hive, plus maybe a few pounds of honey, when it comes time for that. If you’re local to me (in the MD/NoVA area) and interested, please email me and we can discuss it!