One of the things I find most interesting about my brewing hobby is the various rabbit-holes it will take me down. The research takes me down all sorts of odd side-streets and alleys.

Rabbit Holes

For example, finding myself with all sorts of “excess”–mostly spent grains–I started looking at other things to do with it. Dog biscuits and bread are the obvious answers. Or when a batch is done fermenting, I’ve got a surfeit of yeast: again with the bread.

Then there are the slightly odder things. What did they use to drink their beer, or ale, or wine, or mead? That question led me to a number of interesting places. There’s the bowls and cups I mentioned previously–those tended to be for beer, sometimes ale. There are lots of references to “wine cups,” and the Russians even had a “wine bowl” of much larger size.

Drinking horns? Well, they were used, but I don’t think they were ubiquitous. (There seem to be many more trees than there are horned livestock.) Tankards? Possibly. Probably, even. I’ve seen reference to lots of glassware, too, and its use seems to have spanned class and caste to a much greater degree than people think.

Then there’s the question of mead. It seems to have been very much a special occasion drink in most areas. For that, you’d break out your “fine china,” in the form of your horns and the like. One particular type of vessel stands out for mead, though: the mazier. (It’s also spelled “maser,” but using that as a search term brings back all kinds of odd sci-fi stuff.) Maziers, though, are worth a post all their own.

Where things get really interesting to me, though, is when you can actually look at an extant item. That’ll usually be through photographs, to be sure, but it’s certainly better than nothing. (One interesting source of photos is Robin Wood’s book “The Wooden Bowl”. This book focuses on central and northern European bowls, and has lots of lovely pictures–but it’s not where I’m going today.)

Enter Trossingen

A set of turned things that really caught my attention when I first saw pictures of them were the wooden goods from the Trossingen grave. I don’t recall how exactly I ran across them–most likely, it was wandering through Pinterest–but detailed photos and descriptions can be in the book “Mit Leier und Schwert” by Barbara Theune-Großkopf. (The link to it is here, but be forewarned that it’s Amazon.de, the book is in German, and it’s usually out of stock.)

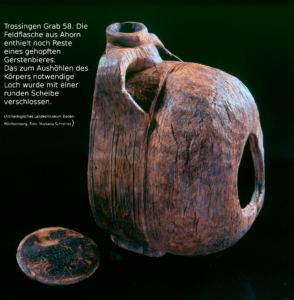

The grave is that of a 6th century Merovingian/Frankish high-status warrior. He was buried in a box-bed turned into a coffin, surrounded by grave goods, to include his sword, shield, spear/lance, a lyre, an antler comb, some pouches, a chair, a small table, candlestick, some candles, two bowls, and a canteen. Of these, the bed, candlestick, chair, table, bowls, and canteen, were at least partly turned.

Now, those are enough to pique my interest all on their own. But what really grabbed my attention was when I read through the bit on the canteen. In particular, the fact that the canteen was probably full when it was buried, and there was still residue on the inside–which they ran a pretty full analysis of.

Alamannic “Starkbier” with Honey and Hops

Apparently, the Trossingen canteen once contained a fermented malt-based beverage, strengthened with honey. But where things get really odd is when they looked at the various pollen grains that were present. Among other things, these included hop pollen.

Being good scientists, and Germans to boot, the researchers decided to get together with the Weihenstephan brewery and try to recreate the beer. The report on this was published in a different academic journal, which I’d have to track down separately. If/when I find it, I’ll update the post and put a link to it here.

The recipe was obviously speculative–they were going off of long-since-evaporated 1300 year old dried beer residue. I’d like to see a little more about their process, and probably make a few adjustments to it. For instance, I believe the “recreation” used purely modern barley-malt. Hand-malted, to be sure, but more than likely the period malt would have included wheat and rye at least, possibly oats, and maybe some other weed seeds as well. Small percentages, probably, but it doesn’t necessarily take much.

Nevertheless, they came to the “definitive” conclusion that the canteen was full when buried, it contained a strong barley-based fermented drink. That drink was hopped, and at some point honey was added.

Let that sink in for a minute. They’re talking a hopped beer in 580AD. This is pushing 250 years before Abbot Adelhard of Corbie Abbey wrote, connecting the hop-harvest with brewing, and 600 years before the earliest written evidence of hopped beers in the modern sense, from St. Hildegard of Bingen. (Read about Adelhard and Hildegard over at Zythophile!)

My mind was, to say the least, blown. But still…

What Does It Mean?

How, you may ask, does this affect my brewing? Well, to be fair, it doesn’t, really. I mean, if your persona in the SCA runs to early Frankish or Germanic, it means that hopped beers are “allowed” (not that that was stopping you). You’re not “stuck” with gruitbeer (which is a topic for another post). And speaking of other posts, we’ll take a look at the bowls, candlestick, and chair in time.

This has me wanting to do another experimental brew on a future Brew Day, to do my own recreation of the batch. What say you? I’m open to questions (and suggestions) in the comments!